Climbing Mount Everest, 8848m, in 2003

- David Young

- Nov 26, 2024

- 8 min read

Updated: Nov 28, 2024

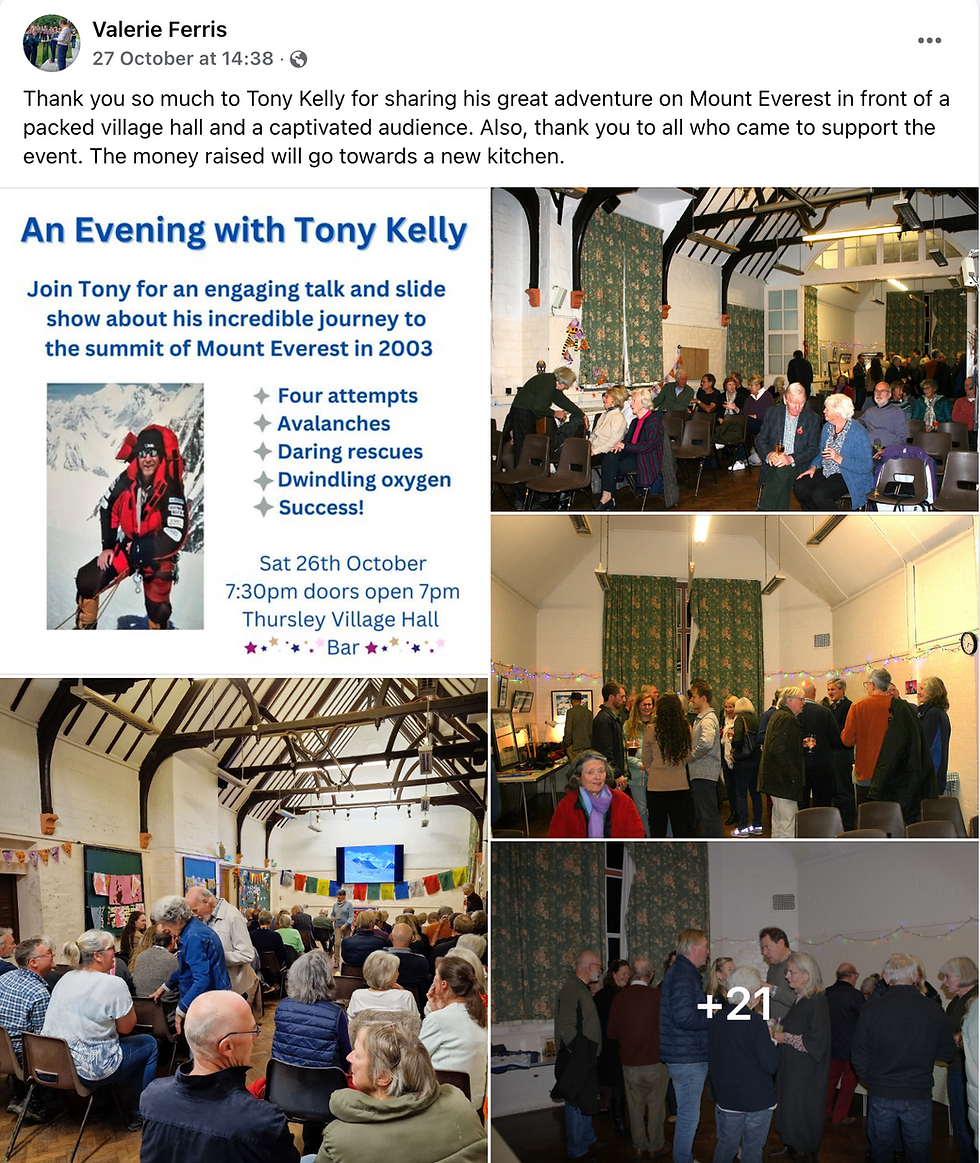

Tony Kelly, of Bedford Farm, gave a talk in the village hall in October 2024 about his extraordinary feat. The text and the ppt below are condensations of his talk which was appreciated by the packed audience.

From Thursley Village Facebook page:

Climbing Mount Everest, 8848m, in 2003

The highest point on Earth. A summary of Tony Kelly’s story

The presentation will cover the lead up to the climb and our summit bids. I’ll also touch on some history of the mountain, as in 2024 its 100yrs since the famous 1924 Mallory and Irvine Expedition (and the mystery of did they summit or not). Their route was on the North side of Mount Everest and we are attempting the same North side route from Tibet. We are attempting the north route because its technically much harder than the south and consequently climbed much less. Back then around 1200 people had summited Mount Everest but only approx. 200 of them from the North side.

It's worth dwelling on George Mallory and Sandy Irvine briefly. Mallory’s body was eventually found on the North Face in 1999 with torso bruising indicating a serious fall whilst roped. The remains of his mid layer jumper were still visible supplied by W Paine, 72 High Street, Godalming. Yes, he was a local. Originally from the north west but settled in Godalming as a teacher at Charterhouse and married Ruth, a Godalming girl. Sandy Irvine’s remains were only found in September this year, 2024, on the north face directly below but much further down than Mallory’s body indicating they were almost certainly roped together when they fell. I will also bring to the talk a section of telegraph wire, used for Advanced Base Camp communications in 1924, that I found on the East Rongbuk glacier in 2000. I was with Graham Hoyland at the time (he was on our 2000 expedition) who had been responsible for the search that found George Mallory in 1999. Graham was the great great grandson of Howard Somervell who was on the 1924 expedition with Mallory and Irvine.

So where did it all begin for me? After hiking in the UK through my 20’s I got introduced to rock climbing and quickly progressed to rock, ice and mountaineering in the Alps. After 10 years of multiple annual trips to the Alps, I was looking for a bigger challenge and met the internationally renowned expedition leader, Russell Brice, in a bar in Chamonix. My friend and mountain guide, Mark Seaton, was able to reassure Russell I was technically more than competent to join him but we didn’t know how my body would react to extreme altitude.

In 1999 I went with Russell Brice to Cho Oyu, the 6th highest mountain in the world at 8,188m to find out if I was ok at altitude. As a test it went well. The weather was brutal. In the end we didn’t make a summit attempt because of extreme snow conditions but I was the only member of the expedition, westerner or sherpa, to reach the expeditions high point of 7,900m and I did it solo. Mt Everest was on!

I had mentioned, summit bids, plural. In 2000 we took an expedition to Mount Everest to climb the North side from Tibet. After 2 months on the mountain we made 2 attempts on the summit. The first one was aborted at 7900 metres due to atrocious weather conditions and massive snow loading. That first attempt had high attrition and resulted in 6 of the 7 climbing members pulling the plug. Consequently, on the 2nd attempt, it was only myself, 3 professional mountain guides and 3 sherpa’s that made the attempt. At camp 2, 7500m, our tents got avalanched overnight and buried. It became a matter of survival, avoiding carbon dioxide asphyxiation overnight by punching holes through the snow and ice over the tents and the following day using a quite dangerous technique to deliberately trigger avalanches to clear the massive snow load in front of us to be able to down climb. To cap it off in our exhausted state when we pulled off the mountain a melt water lake had broken out of the East Rongbuk Glacier and we had to build a raft out of barrels and wood to ferry the 20 expedition members and 10 tonnes of equipment out! I’m reminded of the definition of an Adventure: “an undertaking with an uncertain outcome”!

So the 2003 Expedition was “Unfinished Business”. We returned to Kathmandu, Nepal, in late March and after assembling some 11 tonnes of equipment and “shopping” in the local markets for 2 months plus of provisions for 17 team members we made our way via Lhasa, Tibet to Mount Everest basecamp at 5200m and set about the expedition proper. High altitude climbing is a combination of technical competence, mountaineering experience and a “head game”. It’s a marathon not a sprint. You’re going to spend months in daily calorie deficit, physically and mentally stressed by the environment and the challenge. -50 deg C and 150mph winds are regular features. You’ll spend a lot of time climbing at 10/10ths of your ability and experience but to be successful you will have to spend some time at 11/10ths or worse and make the judgement call on when to take those risks and how long to stay exposed. Tenacity, stamina and will power will count for a lot. On arrival at basecamp team members blood oxygen levels of mid 70% were not unusual. That would be an A&E visit back home at sea level. Acclimatisation to get the blood oxy levels into the 90%’s takes weeks as you teach your body to produce more red blood cells to cope with the ¼ of sea level oxygen availability we’ll have to deal with higher up the mountain. Acclimatisation starts in base camp knocking off 6000m peaks to warm up and then moving up the glacier to work on the mountain.

The route will take a month and half of preparation work putting in fixed rope and installing and provisioning four high camps. We’ll be going up and down visiting and revisiting these camps. This will mean we will effectively climb the height of Mount Everest several times in the process before we even consider a summit attempt. The north side route is not only technically more difficult than the south side by it is much longer. Its 22km from Basecamp to Advanced Basecamp. From ABC we must establish camp 1 at 7050m, camp 2 7500m, camp 3 7900m and camp 4 at 8300m and fully stock them. That includes lugging oxygen bottles (about 6kg each) up which we will use (3 each) from camp 3 7900m onwards. The climbing is a mix of technical ice climbing and massive snow slopes, rock sections of scrambling and massively technical vertical rock climbing at 8600m on the 2nd Step (this is the crux of the climb). Having got the infrastructure of the route set up we had to retreat to base camp because of a massive storm. It wiped out a significant portion of our camps on the mountain ripping tents stocked with personal kit, food and oxygen off the mountain and depositing it on the glacier below. When we went back up to ABC we had to find the debris on the glacier and icewall, extract it from crevasses, uncover the snow buried ropes, rebuild the camps and route. (when l say “we” went back to recover things it was actually only 2 of the 7 client climbers (Trynt and myself) together with sherpas).

We then set about a summit attempt in late May. Two of the seven climbers pulled out sick. The rest of us pushed on. Five climbers with sherpa partners and a mountain guide. Herman, the guide, was focused on Zedi, Matt and Gernot. Sue and Chung were sick. Myself and my sherpa partner, Dorje, were operating pretty much independently. It’s typically a six-day push, four days up and two off. Leaving camp 4, 8300m, at circa 10pm/11pm to climb through the night. Intending to reach the three steps on the north east ridge by dawn. But we experienced some delays en route due to some slower expeditions blocking the route in front of us. It wasn’t busy like photo’s you may have seen of the south side but this was 2003, the 50th anniversary of the 1953 success, there were a few more climbers than normal and its the nature of the route on the north that is much more constraining. I got further delayed by having to rescue a climbing colleague (Zedi) who made a massive error and found himself hanging on the rope at the 2nd Step, 8600m, swinging over the north face of Mount Everest with a mile of fresh air between his legs. It cost me, and Dorje my sherpa partner, a lot of excess oxygen usage fighting to save him. We got him back in and back enroute. It took Dorje and I a while to sort ourselves out and get going again. The others, including Zedi, who I had rescued, were ahead and summited, albeit late (having breached the turnaround time limit we had all agreed to). I calculated I was about to run out of oxygen probably on top and that would risk death. I made an incredibly difficult decision to turn back 48metres from the top which would have taken another 1.5hrs! I radioed Russell to advise and we turned back. On descent I did actually run out of oxygen around 8500m but we still had to get down so Dorje and I pressed on without. We also had to help rescue (again) the same guy I had recovered on the way up because now he had gone snow blind and couldn’t see to down climb. The climb was incredible but a massive blow to turn back so close.

After getting back to Advanced Base Camp and feeling pretty low the next morning Russell came to my tent with a mug of yak milk tea and a large shot of whisky and told me to shut up and say nothing. He said everyone else is leaving, there’s a narrow weather window opening and I think you have it in you to go back! Basically he convinced me to attempt what no climber (professional or amateur) other than a small number of sherpa’s had ever attempted on Mount Everest and that was to climb the mountain twice in one season and I was going to try twice in two weeks!

So nine days after returning to Advanced Base Camp Sue and Chung, my colleagues who had been sick on the first attempt and myself together with our sherpa climbing partners mounted what was to be my second attempt this season and my fourth summit attempt on Mount Everest. The weather was going to be challenging. We didn’t have the requisite four days up and two off. We had to wait out a storm in Camp 2 and then pushing very hard from camp 2 we missed out camp 3 by a continuous climbing push stopping very briefly at camp 4 (not for rest, food and sleep as normal) we picked up water and oxygen and continued climbing into a 33-hour continuous aggressive push right through the night to summit early in the morning, for me at 7:03am, May 31st.

It had been amazing as every other expedition except ours had left the mountain so Sue, Chung and myself had the entire mountain to ourselves. This is unheard of and although we had climbed through a storm the summit day was blue sky with the curvature of the earths horizon visible for a 100miles. There were tears. Which immediately froze!

Getting up is of course only half way. Getting off is essential and almost as hard as going up. In my case very hard having only nine days prior albeit but for 48metres been on the summit. It becomes a massive head game. Your body is screaming for rest telling you its done in and there’s nothing not even fumes left in the tank. You want to stop. But if you stop and rest there is a very high chance you’ll slip into dozing followed by hypoxia and then hypothermia and death. So keep moving. I made it back to camp 1 at 7050m and rested for the night before descent to ABC the following day.

2003 was the 50th anniversary of the 1953 successful first summit by Hilary and Tensing via the South side Route and associated with that anniversary the Nepali Mountaineering Association were at the 2003 Kendal Mountain Film Festival awarding medals for significant achievement on Mount Everest. I was on stage in the company of Chris Bonington and Doug Scott (1st brit), Stephen Venables (1st brit no Oxy) and others including Mike Westmacott and George Band members of the 1953 expedition. I was awarded a Gold Medal with the citation from the NMA president: “an outstanding rescue, wise turn around at 48m, subsequent success after only nine days and in aggressive style, extraordinary & exemplary mountaineering”